Phil’s Last Dance

“I don’t often do this,” my boss said, “but I’d almost insist on you watching The Last Dance. Let’s talk about it afterwards.”

My boss used to be a pretty serious basketball player. He often makes basketball references. “You cannot always be Pippen,” he’d say, “sometimes you have to be MJ.”

Solid advice! If... well, you know who those people are, and what they represent.

To get the right vibe while reading the rest of this post, and to ensure you have the proper experience, be sure you play “Step into a World” by KRS-One in the background. In a loop. Ad nauseam. It’s part of the experience.

In fact, to really optimize the value out of this email, simply watch The Last Dance right now. It’s just 10 hours. I’ll wait.

Back? Cool. How was it?

While watching it myself, I realized I completely forgot how big of a deal The Chicago Bulls and basketball were during the ‘90s. I was in primary school at the time, I was not attracted to sports in any way, but I played basketball with friends. I had a Chicago Bulls cap. On the Gameboy that me and my brother saved up for, NBA Jam was one of our first games. And one of the first VHS tapes we bought was Space Jam — best movie ever, if you haven’t seen it let me sell you on it: Bugs Bunny, Michael Jordan in space. I know, right? Solid winner.

Also, honestly, simply watching those basketball moves, dunk after dunk, with KRS-One in the background is just... cool. It’s just cool.

If only software or management was 10% this cool. It isn’t.

But this is not a site about random Netflix shows (yet). So, why would a sports documentary be worth watching as a person interested in managing engineers?

One of the things that makes engineering management interesting to me is the sheer amount of dimensions to it. Based on the challenges you face day to day you’ll be sucked into sometimes the people topics, sometimes the technology topics, sometimes communication topics.

And then, you watch a Netflix show, and you’re reminded of a management topic that wasn’t completely top of mind, and you start musing on it: am I thinking about and doing enough in this area myself? Can we apply lessons from basketball to the world of software?

So what is that area in The Last Dance for me?

Coaching

If you look at the three key players in The Bulls (MJ, Pippen, Rodman), none of them by themselves would have been enough to win all those NBA championships. Not even MJ. It wasn’t the act of scouting and recruiting those three guys into the team either. Nor was it just putting these individuals into one team. Obviously, there was a huge amount of potential created there, but that potential needs to be tapped, and this is the role of the coach.

This is completely relevant to software teams. You, as an engineering manager, recruited, inherited or through some other means got a group of individuals handed to you. Now, how do you turn that group of individuals full of potential into a coherent, productive team? Honestly, that’s a pretty succinct job description of what is expected from an engineering manager. There’s many tactics to this job, but coaching for sure is a vital one.

It’s my impression the sports world is far ahead of our industry when it comes to mastery (and appreciation) of this coaching role. Over the last years I’ve read a good few books about coaching, many coming from sports people: for instance The Score Takes Care of Itself (by baseball coach Bill Walsh) or Leading (by soccer coach Alex Ferguson). Even the coach that had the biggest impact on Sillicon Valley, Bill Campbell, had a college football coaching background.

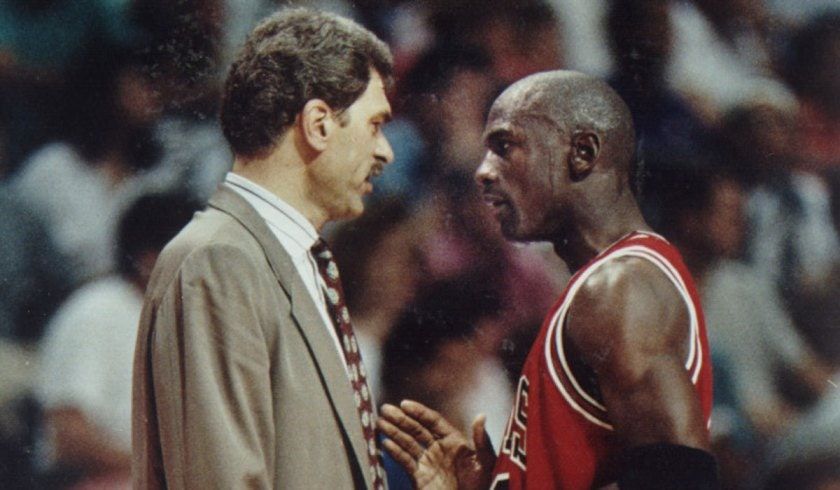

So, while you thought you were watching a documentary about Michael Jordan, the real hero of the story is Phil Jackson, their coach. You didn’t realize? No worries, neither did the makers of the documentary. Sadly.

Phil’s challenge

Here’s the Phil Jackson challenge translated to our world:

Imagine your employer hired the world’s best software engineer. To draw the parallel with MJ, let’s say this this is a he. He’s insanely talented. Productive. Smart. He knows he’s good too. Also: as a result, he’s (excuse my French) kind of a dick. Yes, a brilliant jerk.

Now let’s assume you need to embed this engineer into your team (I’m not sure this be the go-to scenario in our industry, but let’s assume). Luckily, your employer hired two more extremely talented guys (and a bunch of extra “padding”).

The second person is a real team player, also extremely talented, originally hired as an intern and therefore significantly underpaid. He knows it too. Due to COVID, you cannot raise his salary. He’s pretty affected by this, and acts out from time to time at unpredictable times.

The third person is another go getter. He will get things done through sheer force. He’s also quite a character, and not extremely reliable. He parties hard, ends up marrying a Baywatch actress, and may sometimes just disappear for a few days “to blow off steam.” When he’s there, though, he brings the value.

“You’re welcome,” your employer says. “These are some of the top people in the industry. We expect great things from them! If you don’t make it happen, no worries, you’re — how does Trump put it — just fired.”

In addition to these guys, you have a bunch of other people in the team. They’re pretty amazing too. In other teams they would be the top players, but with those other three guys around — they play second fiddle. And they know it, with varying levels of frustration. Some may threaten to leave the company if they don’t see a path to the top, and some actually do.

This is the Phil Jackson challenge. Enjoy!

As mentioned, our insight into what Phil Jackson was doing behind the scenes is limited, as this is really an MJ documentary (at least the documentary makers thought so, so that’s how it’s structured).

We do learn a few things though.

One, Phil spends significant time with his players one-on-one, coaching them to be their best-possible self.

Probably the most visible accomplishment here is that Phil, somehow, manages to convince MJ that he actually needs his team for more than just passing him the ball whenever it’s not already present in his hands. He’s teaching him to rely on his team, and sometimes handing things over to them to get them done. You can tell this is hard for MJ, but you can see that the championship winning only starts when he gives more to his team and relies more on them. And then, from time to time, in key games, the deciding shot isn’t made by MJ but by other people in the team.

I’m sure Phil Jackson did similar work with with Pippen, Rodman and the rest of the team. Jackson’s approach to each, for sure, was 100% different. MJ is no Pippen, Pippen is no Rodman, and Rodman is... skipping his 1:1 time with Phil, because he’s wrestling with Hulk Hogan.

Whenever it comes to coaching, I’m reminded of this quote from the Trillion Dollar Coach — a great book about Bill Campbell, founder of Intuit and later coach to a shocking number of big names in Silicon Valley (emphasis mine):

When Brad Smith took over as CEO of Intuit, Bill told him that he would go to bed every night thinking about those eight thousand souls who work for him. What are they thinking and feeling? How can I make them the best they can be? Ronnie Lott says, when talking about two coaches he worked closely with, Bill Walsh and Bill Campbell: “Great coaches lie awake at night thinking about how to make you better. They relish creating an environment where you get more out of yourself. Coaches are like great artists getting the stroke exactly right on a painting. They are painting relationships. Most people don’t spend a lot of time thinking about how they are going to make someone else better. But that’s what coaches do. It’s what Bill Campbell did, he just did it on a different field.”

So, individualization is the first task of a coach.

The second thing is bringing the people together as a group. Sadly, we don’t get to see a lot about this in the documentary (other than some yoga session shots), but I found a New Yorker interview with Sam Smith (journalist also appearing in The Last Dance, the guy that wrote the nasty “Jordan Rules” book) with bit more insight:

One of his Phil Jackson’s strengths that was often overlooked or unappreciated was this great ability he had to bring a group together. He grew up in congregations. His parents were Pentecostal ministers. So he treated his team like a congregation, and with a combination of being aware of the needs of the individual while also promoting and celebrating the group. I wasn’t in a lot of the yoga sessions, but I’d be on the bus, and we would be in, like, Seattle. And he would go, “We’re going to Portland.” Everybody else flew. He said, “We’re going to take the bus, because I want you guys to see what the countryside is, the beautiful countryside up here.” So we’re taking a bus from Seattle, we’re getting off, having to eat.

This has changed in modern NBA life:

Nothing like that exists anymore. They have their own trainers and they have their own staffs, and they don’t even want to work out with the team half the time.

So:

- Invest deeply in your team as individuals: lose sleep over how to make your people better.

- Invest deeply in making your team work as a group.

Easy.

Think about how you can be more of a Phil to your team.

PS: I never realized is how much teams like The Bulls at the time were built around a single star. A lot of the “team work” seemed to be (at least initially) focused on “how do we get the ball to MJ?” This is such an anti-pattern in our line of work. We constantly ask: where are our bottlenecks, how do we remove them? Bus factor, bus factor, bus factor! No such question seemed to be the priority at The Bulls. Luckily, Michael Jordan was such an insane talent that even with food poisoning and high fever he was able to perform his bottleneck role. Yay, I guess?

Speaking about the documentary with my boss afterwards, he gave some background about how different teams in the NBA have different strategies around this. Some, like the Bulls at that time, indeed built their team around a single superstar. Then, when that group is no longer sustainable, e.g. due to cost or simply because they get too old, the whole team is flipped over and “rebuilt.” Other teams have more of a long-term sustainable model, where new talent is constantly brought in, slowly groomed to take over from other players. There’s a clear succession plan and strategy.